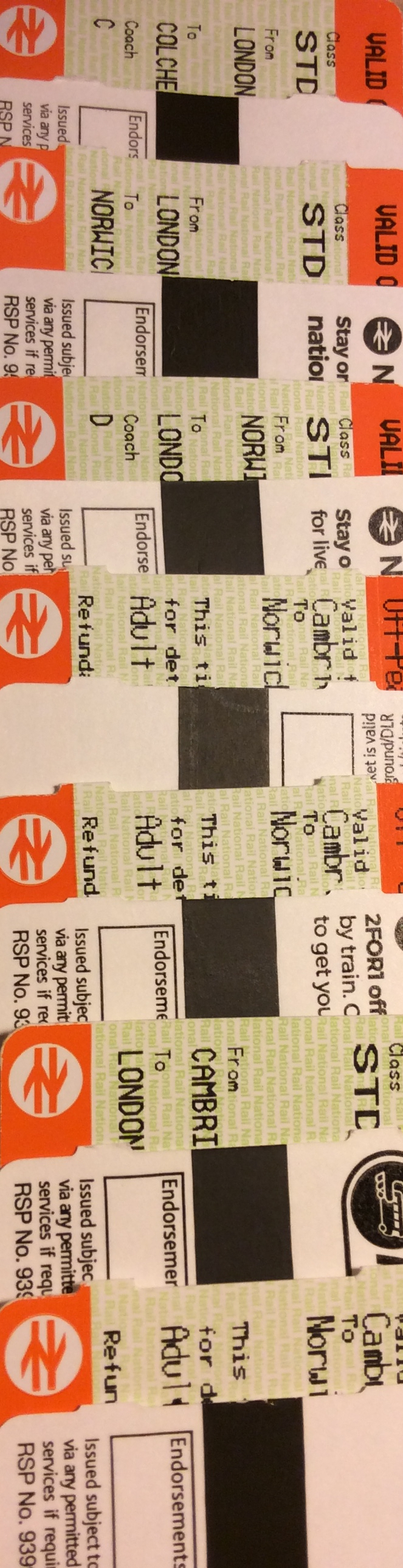

Easter holidays in Greece are the perfect time to write. Unlike the picture above, taken only about a month or so ago in icy Norwich, I can sit in our garden, and stare at an empty word document as long as time permits. My creative process if fuelled by Greek weather and Γεμιστά (Gemista), which, for those of you who don’t know, are stuffed tomatoes and bell peppers that truly make one believe that foodies have it better in life.

Seated in the garden, rested and ready to write, the page remains empty and I pack my laptop up, and head inside. I’ll write later- after a few days, a nap, a long walk in the centre of Athens, a few too many episodes of ‘Easy’ on Netflix, a myriad of internship applications (and a packet of Oreos), under the familiar artificial light that makes me wish I was a morning person. It’s comforting that my laptop is still running on U.K. time…

∗

I am always trying to wrap my head around what it means to have empathy. I have, on occasion, known empathy to be an awkward experience. As you grow into and out of your loss, times in need of empathy are filled with words that are too heavy in their own hollowness. It feels like trying to handle a stuffed animal that is too bulky, making it difficult to lift and carry around, much more to hand over to someone who needs to be comforted. Here you have these experiences that fill up the room, the whole house, and people cannot find a single thing to say that can help in cleaning up the mess. I’ve come to realise that we demand of people to be empathetic in a certain way that we deeply need. In my experience, the trouble is that often empathy is so much more about the empathizer than about the person on the receiving end. For this reason, as a person who has been (and hopes to always be) in both positions, it is so difficult to navigate the topic of empathy without being critical of myself and of others- which is, paradoxically, the very thing that must be done.

∗

As a person grieving, I have felt the many textures that are traced through the experience of needing to feel empathy. I have felt that grieving is not a flexible process. I have felt like certain words needed to be stitched through a very specific part of the tear, weaved in with waves of a particular person’s voice. I have felt what it means to expect this precise version of empathy and not receive it. Often, the voice that came was not the right one, the attempt fruitless, at the wrong time, not in the shape that fitted my size of grief. The realization that people do not always carry your shape of empathy is unsettling; to discover that you too are prone to leaving others barefoot in the face of their pain is even more confusing. Grief is unstable as it is destabilising- an evolving experience in which growth and immobility are concurrent processes. In the face of empathy, we are all children outgrowing their old shoes faster than our parents can afford.

I tell my friend that I think of my experience as one that is split down in the middle, at a strange angle. Ironically, my words come out as if I can see a clear before and after. ‘What do you define as post-grief times, then?’, she asks as we are perched up on my couch. I smile because that is a very perceptive question, perhaps unintentionally intimate. It’s one of those questions that catches you in a personal moment where you are carefully balancing your reality between distinctions- then and now, ‘pre and post grief times’. This imagined reality is miles away from the one I have felt. It is my experience that loss lies one moment in feeling your grandmother’s soft hands, and the other in walking past the launderette where someone is washing their clothes with the detergent your mother used at home when you were a child. One day your life is dominated by these moments, and the other, still learning how to move again, ready or not, you must run over to someone who needs you more than you need yourself. The distinction is blurred. Empathy becomes a rope of which you can see both ends, and both are tugged at to stabilise both yourself and the person on the opposite end.

∗

This past year has seen people I love in loss. Barefoot, I am trying to navigate the game of empathy, and I am full of blisters. I say the wrong things, feel myself questioning when it is right to break the silence, send a message, call, knock on the door. I am an unexpected visitor in someone else’s sadness, and it can be so uncomfortable. What are the right questions? Wasn’t I supposed to know some of this from my extensive experience in the field of grief? And, at the same time, I ask: am I not the person who stresses the individuality of each experience?

In realising the fragility of these situations, I am choosing to ask questions without treading over them with my own assumed knowledge. I promise that I will always take my shoes off in your house if you will let me in.