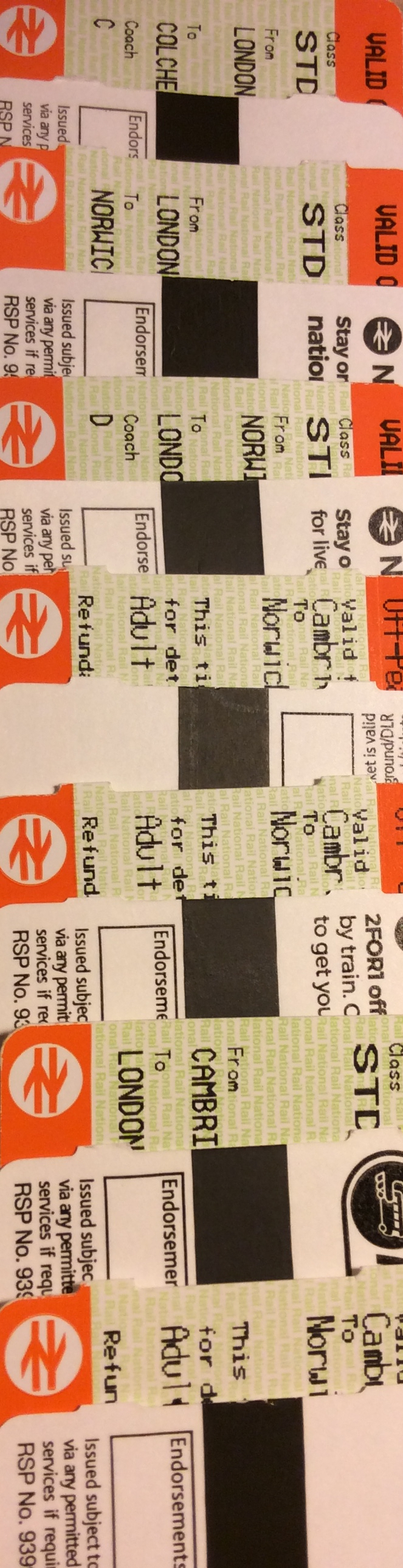

My experience with honest writing is rather commonplace. I will often (but, not always) write the most honest words when I am on a train or a plane. I will get the idea in the shower or when I am doing my dishes. Movement and transitory moments are loud and crowded and sometimes the most solitary and creative. Transportation, in this sense, can be a magnificent reflection on privilege; a place where movement is not a loss.

Honest writing happens during showering. Warm water evaporates and returns replenished: an image of its own possibility. When I write most honestly, my eyelids feel dry and heavy, and my typing rings with a mechanic quality. I am not sipping on tea or gazing out of my window. Maybe someone else is. But I am arm deep in dishwashing bubbles and scrubbing a pan when I think of that which could be written.

Honesty and grief are two topics that are very close friends and spend most of their time together. They are the ones drinking the tea instead of me.

Grief is often a situational experience for me. I always wish for grief to be honest; to explain itself. In turn, I try to demonstrate the ways in which our relationship is like that between me and honest writing. I accept the effort that needs to be put in on my behalf. In return, I ask for the opportunity to do so.

Honest grief lives in the realisation of the things I see myself as incapable to do. Or, rather, it is caught between the moments in which I begin to believe that the object of my grief could have shown me how to do things better. That which I have lost would have dealt with the situation better than myself. In these moments, I get a glimpse of an object which is steeped in the grief itself. A thing of warmth, like laughter, and I am set in a process of searching through disorderly moments of the past for a more tangible experience to bring me closer to the new feeling.

This grief, although lacking in a clear definition, is honest. It speaks in the language of needing to cope, and not in terms of detachment. I think of the person’s favourite books; perhaps, I can read something that revised their understanding of the everyday. If this does not work, I could emulate their handwriting style so that my words, even in appearance, can form an attempt to resemble their own.

The grief of these needs seeps into me involuntarily because of their honesty. They have not yet seen themselves dressed in retrospective tulle and silk. I have not met them in official attire. Our encounter has been utterly informal; they have seen me do the dishes.

∗

I have been writing a piece on my grandmother. It is taking time. And I thought I would not post anything for a while because it didn’t feel like the right time to do so. I do not think that it is necessarily a good thing to wait for the perfect moment to write. As most people know, these instances are deliciously rare, and you will not get your degree if you wait for them. What I’m getting at is this: although I did not want to write anything before I finish the piece I am currently working on, I would like to celebrate and applaud my own moments of writing spontaneity.

Sometimes, in order to write, I need to take a lot of time. In these moments, I sit on my chair and feel the texture of the thoughts once they have settled. Only when I have done this can I expect the words to cooperate. Even then, they often form sentences in fragments, to be constructed and deconstructed in the process of editing.

Most of the time, these will, in fact, be the best pieces I write- I know this. Pieces well researched, well thought out, with both time and planning invested in them; the obscuring clutter around them is tidied up and put away. Yet, there are other times when writing can feel incredibly honest to me when it begins on the train, or next to the kitchen sink. I will clean it up in the end as I would the others, but it will be stained with soap marks that do not go away.

These are fleeting moments which move me in writing and in grief. They consist of the matter which gives writing a human voice. Together, grief and honesty web an authentic mess that spreads and links the iPhone keyboard with overwhelmingly personal feelings. Like this, I see the words hold hands with grief.

∗

I am on the train, and, in all honesty, my eyelids are too heavy to keep open any longer.