When I was around ten years old, we went on a school trip that is significant for me to this day. As part of an assignment, our teacher took our class- the prestigious Year six, oldest of the youngest- to an elderly home. This prospect was exhilarating. It meant I could attach the stories of entire life times to people who had the capacity of having lived them. Even the idea of this roused in me the deepest sense of excitement. It seems comical to describe my ten-year-old anticipation in this way; retrospect coats colourful childhood memories with its elaborate new descriptions.

We took the bus there. The details packed around this quiver and ring present to this day. When we arrived, we were assigned a small group of three or four, and accompanied by a resident who would show us around their rooms. My group followed a man who was as eager as me to be listened to; I felt attached to him. He told me some details about his heritage. Regardless of what he had chosen to talk about, I felt a great sense of comradeship with this person who was willing to share his story with me.

We sang with the residents, or performed for them; this memory has been worn out. The trip left a lasting impression on me. This was all part of a class exercise: we would write about our experience. I felt so proud to be at home when it came to writing. I was not ashamed or reserved for my writing or of the pride that accompanied it. It did not occur to me that my words might be the ones used by my classmates who wrote about similar experiences. If someone had told me that the boy next to me was describing the same man using similar words and expressions in his work, it would have meant nothing to me. My writing was mine, untainted by questions of storytelling and ownership.

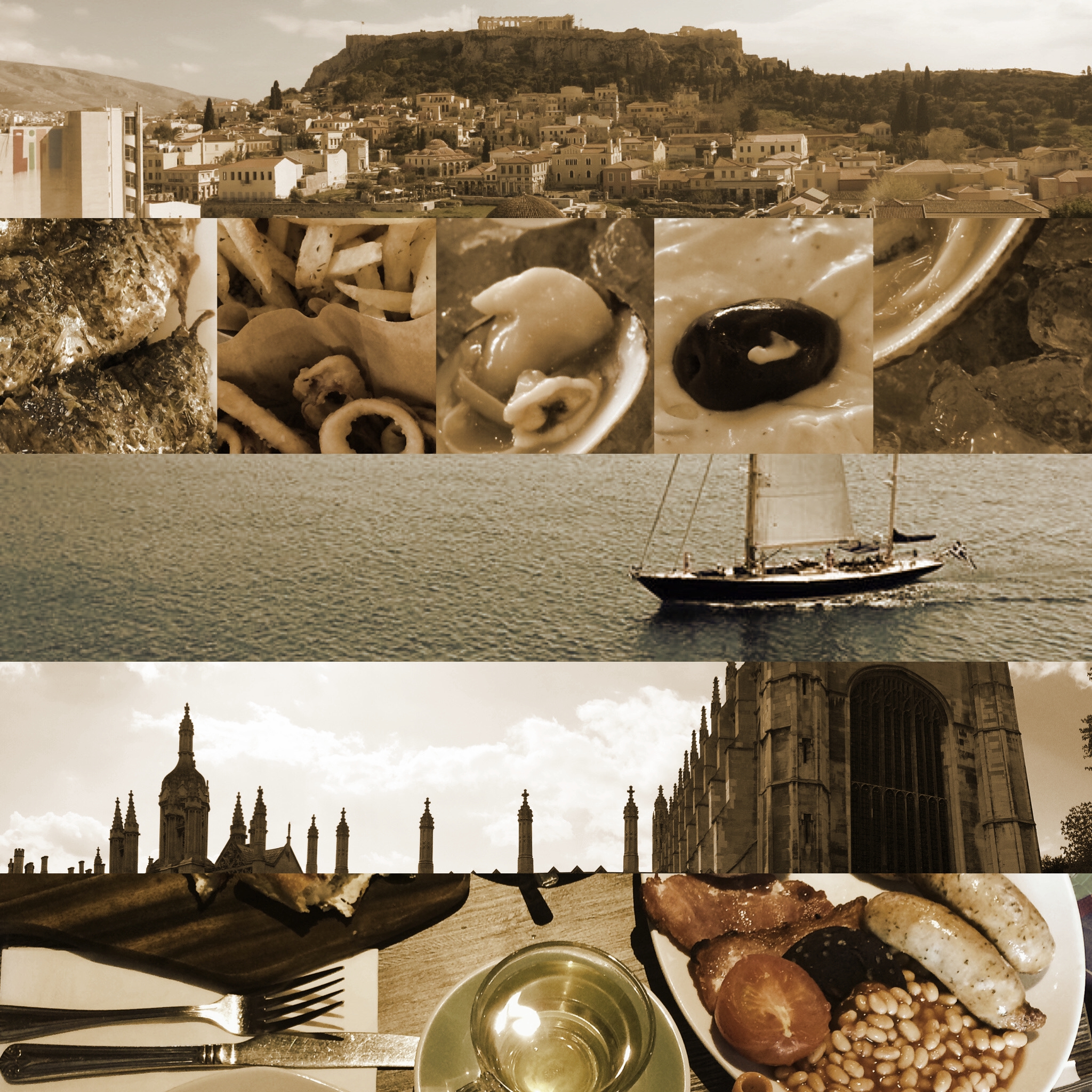

Sometime in the same year, we went on a holiday visiting parts of Spain, France, and Italy with my parents. My teacher had asked me to keep a diary. Most evenings I tucked my chair close to the desk in our room and wrote in the little black book with the strap. I’ve read it since and it strikes me that I did not fear detail or repetition. This small, private freedom indulged me in small pockets of creativity.

∗

Studying at university has made me hyper-aware of the similarities between my writing and that of others. It is a routine to find myself tracing the influence of other people’s writing in my own thoughts; before I write them down they are censored. Don’t get me wrong, I think that being aware of the influences behind different aspects of your writing is a crucial aspect of originality. And, of course, I am not encouraging copying, nor do I believe it is an honourable practice; crediting those whose ideas you are using in academic writing is a core and extremely valuable practice. I am speaking, rather, of the censorship that seeps into the flow of creativity when I become vigilant of those who motivate my own creative pieces. It seems self-evident that influence occurs. Especially as a Literature student, it is more than often that I will find myself echoing the tone of the author(s) whose work I am analysing in my own essay. I am aware that what I am describing is not considered copying. That is how it goes. You read someone great and then you mirror them and that is fine.

Logically, it makes all the sense in the world. Nevertheless, awareness of influence translates into censorship when it seeps into my creative writing. In that realm, it feels different to see the voice of another in your own. When it is a personal piece in which you hear the last book you read colour your tone, it feels unoriginal. You feel like a cheat. I will not try to analyse where this stems from. I have no idea. What I do know, is that I have observed in creative writing as much as in literary criticism that young writers like myself are afraid of starting from the start; of being beginners. This process implies that your voice will carry strong aspects of those that you enjoyed reading or others that have influenced the way you think. In learning to write, we will have to learn to be okay with this; to value it, even. Someone has said that we are afraid of being beginners, I know. Someone must. What was their name again? Influence is infectious.

Then, so much is thrown into the gutter of ‘I have worn this out’. There is a certain fatigue that follows the aforementioned process. Thinking this way about writing, tracing obsessively the influence of other’s work in your own, defeats your will to write and be expressive. It does it to me. I do not want to write about singing with the residents, the story exchanged with the man, or the process of retelling the events. Someone must have done it already. I have thought about it for too long. Following this dizzying train of thought makes you hide in your room with a piercing headache, while your friends sit outside and discuss their pieces, giddy with the scent of someone’s influence running through their own. Maybe, it is worth unpacking why you feel that you will enjoy your piece more when it is finished and you can look at it as the final product.

This particular piece does not end with a suggestion or a solution to this. Someone has one already, I’m sure. But it is worth telling you that I long for the days where I could write about our day in Florence or the old man. He was not only Turkish. He was Turkish and Greek. What is the word for that, again? Someone had told me.