It was a surprise for the literary world when the judges of the Booker Prize decided that Bernadine Evaristo would be sharing the prize with the author of The Testaments, Margaret Atwood. Her novel, Girl, Woman, Other, for which Evaristo was nominated, takes the reader through the lives of twelve, mostly black women and non-binary individuals whose lives are inextricably linked to each other’s, and to the external, mostly British worlds in which they exist.

One of the great strengths of this novel is how interesting its characters are. Each person is profoundly different from the other, although all are bound together in some form: they are of different ages, backgrounds, sexualities and genders. They live conventional and unconventional lives as teachers, farmers, activists, playwrights, cleaners, bankers and students.

Together, and each on their own, they explore the different ways of parenting, loving, and existing at different points in time. We meet their lovers, friends, mothers, fathers, grandparents and great-grandparents. We learn how each one of them is, even in the remotest way, connected to the other, and draw the differences and similarities between their personalities, histories, and lived experiences. It is a joy to delve deep into the lives of so many women that are in some ways ordinary, and in others totally fascinating.

The perspective of each character is articulated through the omniscient narrator, who adopts the voice of the individual they are exploring, adapting accordingly to each of their unique personalities. The voice of the novel profoundly understands and represents the consciousness of each character: from the young, lively Yazz, daughter of playwright Amma (arguably the protagonist), to that of ninety-three-year-old Hattie, great-grandmother of trans activist Megan/Morgan.

The text has a distinctive style: speech is not marked by speech marks, the beginnings of sentences are not indicated with capitalised letters, and certain words, names, or phrases are often separated from the rest of the text. In this way, the form of the writing echoes the rebellious nature of some of the characters whose stories it attempts to articulate. Or, perhaps, it could be said that the style highlights the act of telling stories that are often ignored as a form of necessary rebellion in itself.

Having said that, there were moments in the book where the narration made the writing feel somewhat forced. The tone often left me considering whether it was the character who I found myself agreeing or disagreeing with, or Evaristo herself, invoking the age-old question regarding the author’s presence in their work. There were instances when I thought: is that how a teenager thinks, or is this how an adult thinks a teenager thinks? More importantly, is this how Evaristo thinks a teenager should think?

Perhaps this can be considered a strength of this polyphonic narrative: the fact that it makes the reader consider whose voice they are responding to, and why. There are numerous instances where the narrative feels genuine and alive, suggesting that it is the characters themselves who the reader is reacting to, not merely the writing or the writer.

Overall, Girl, Woman, Other is a deep, gentle, and at times tender exploration of how our personal and collective histories are intimately linked to those of the women around us.

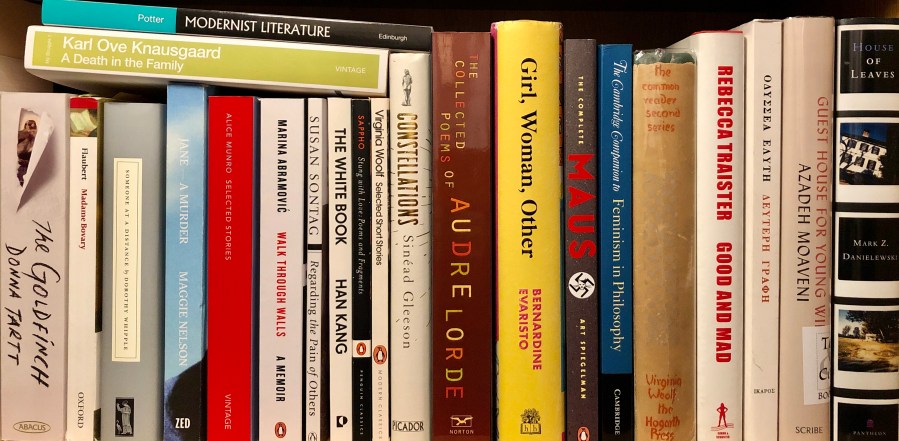

Girl, Woman, Other is published by Hamish Hamilton, 452 pages.