I write this from what used to be the location of my parent’s bed, now my grandmother’s spare room with the twin beds. She kept the sheets on from the past time I visited, a week ago. I surprised her and she told me ‘I knew you would be here again’, and the undertone was hope.

I get in the all- but-cozy position of remembering all you would on your grandma’s twin beds with the strange covers imitating some really odd, familiar form of modern art. The photo album we flipped through with my cousin last week colours the process; I recognise this without interrupting it. ‘I’m okay with this’, I tell no one.

She comes to me through a conscious process which I will be okay with being intentional. I need this one to be lived. She comes in the sepia films. Little white dresses worn at the age of four, five, six. This time, she reminds me of a parcel of sweets we hand out during baptism ceremonies in Greece. It’s a cultural thing, I think. I don’t know the English word, but it doesn’t matter, I don’t need to know it. Maybe you do, but it will be so empty. We can’t do it like that. It’s called ‘μπομπονιέρα’. That’s ‘mpomponiera’, for you.

This is very vague. I give in to the need for explanation. The words ring in my head in the expected language: English. The intention to express plays out as the inability to do so. The language, the pictures, are all next to my mosquito bitten legs, and they could not be more foreign in their strange, new English shoes. They tread all over the intention, really! Here it is, an experience honest and foreign. These pictures of the pale little girl, plump and rosy, are too sepia, too detached.

This life I needed to see is in film, old as well as aged, and in Greek. I imagine it in the present, as a story, told in my new, brightly coloured English. It could not be farther than the plump mpomponiera. That child in pale stockings did not speak my language. It didn’t think of itself as a story. It is now, but mute; only my voice is heard.

My father’s mother was there when I competed in a school competition for the spoken word. I spoke of the power of stories in a language she did not understand. A mute world apart, her and I looked and recognised each other in every word. But, the experience, loaded with emotion, was indeed mute. I trace the guilt through the memory. I didn’t explain to her. My time, not sacrificed, left me mute. Her time was spent absorbing the story I might tell, about stories.

This barrier is complicated but comical because of that at times. My mother imitated a turkey in a grocery shop. We had recently arrived in Istanbul. She was trying to ask for deli meat. The man knew. He got the message and the meat. She took it. Both were thankful for this encounter, for the communication. No language barrier could render my mother silent when in need of Turkey slices!

Once, sat at a place with zesty lemon cheesecake, in one of the city’s most cosmopolitan shopping malls, the waiter said to her ‘Afiyet Olsun’. She came home and told my dad, ‘Giorgo, I must have looked German to him.’ To my mother, this was German, more foreign even than Turkish. We all laughed about it when we found out it meant ‘Bon Appétit’ in Turkish. I still laugh.

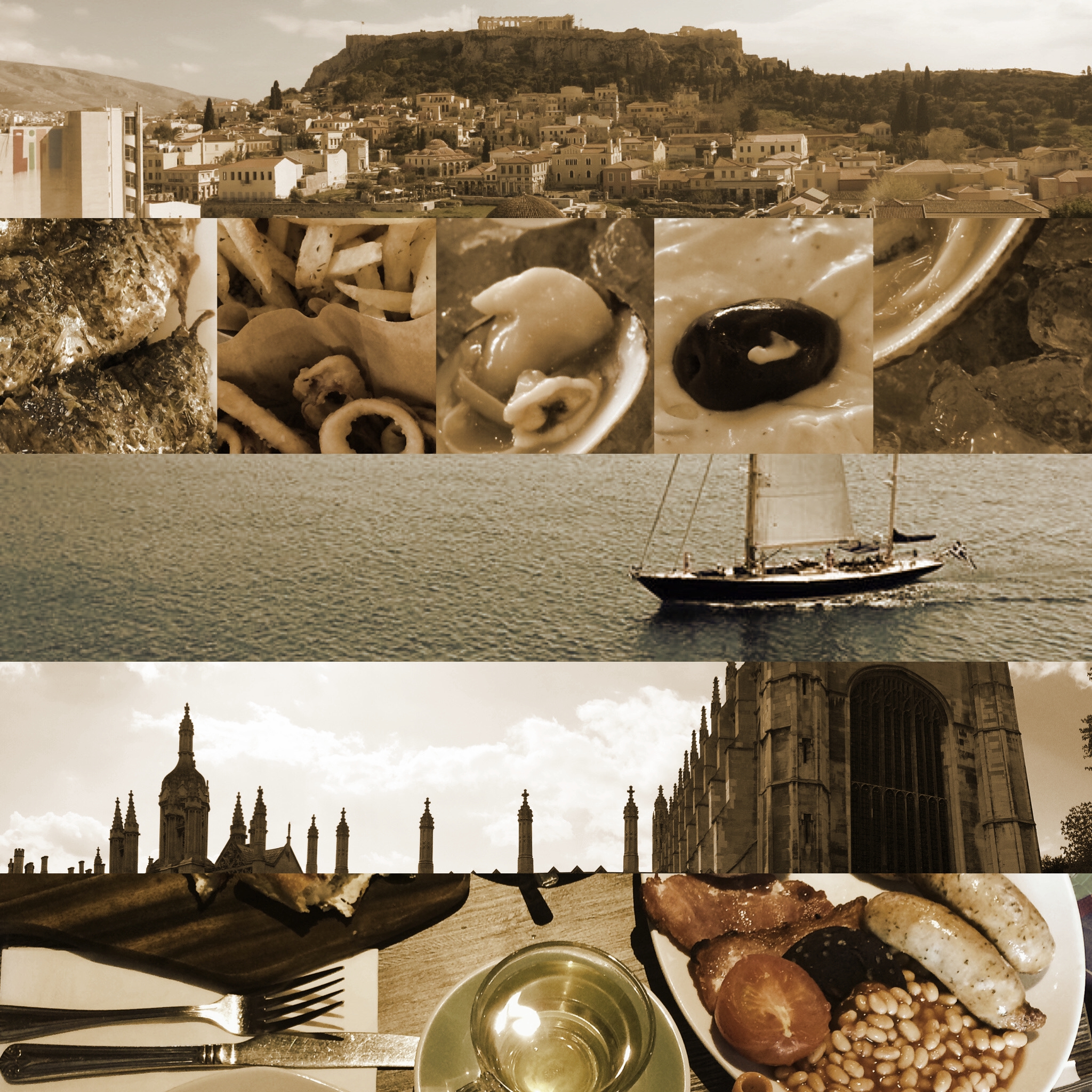

I grew up in a house where I considered as a great personal feat to get my family to speak a broken form of Greeklish. It was, considering the strict rule of ‘Greek only or you’ll forget your mother tongue’ I had to bend in order to achieve this. English became first in a matter of years for me. First choice, first language. Now, I think of how I called my mum ‘μαμά’, ‘mama’, and my thought goes ‘I want to say μαμά again’. In itself, the phrase speaks so honestly of my experience with mixed languages. My memories are tinted with Greek and expressed in English. The filter is the sepia we have on VSCO, the film is from the neighbourhood print shop. Part here, part there. Part Greek, more English, all mine.

This is wonderful – καλή αρχή & please continue!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you very much for taking the time to read my blog post, and for your kind comment, Elena! All the best.

LikeLike